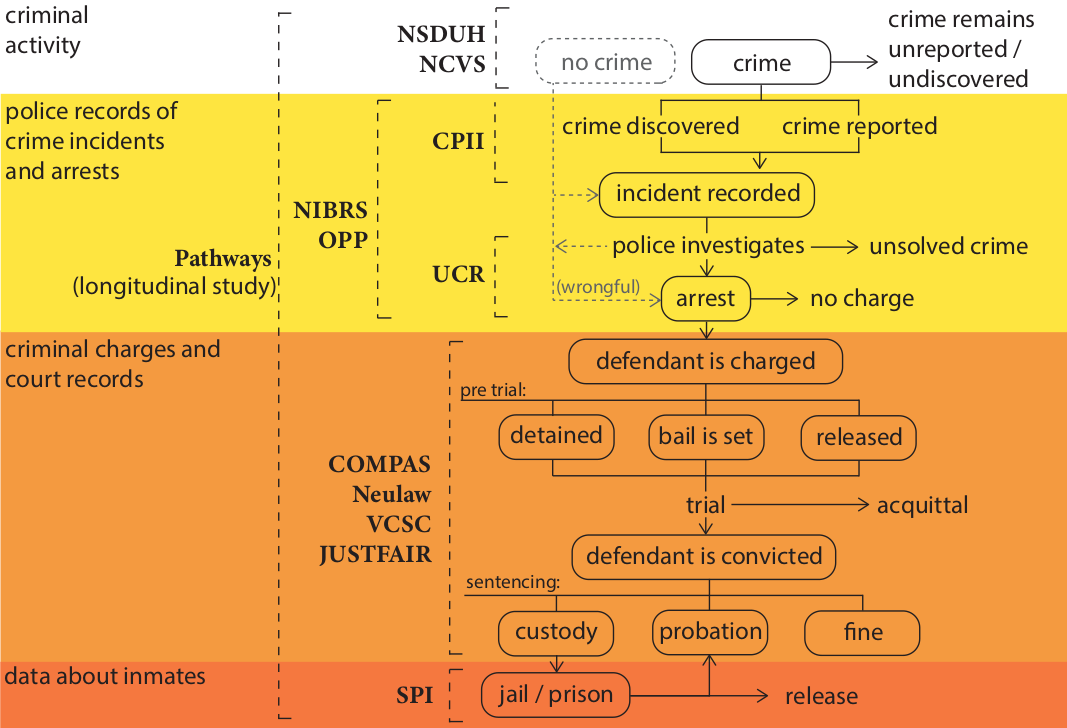

CJ pipeline

Law enforcement can be conceptualized as a funnel-shaped pipeline, beginning with all potentially criminal activity at the top, then progressing down through stages to sentencing, and incarceration at the bottom (see the figure below).12 Here we give a general description of the criminal justice pipeline, providing context for criminal justice datasets.

Starting at the top of the above figure, not all illegal activity is discovered by the law enforcement. There are two main ways a criminal offense can become known:

- reported crime, i.e., police is alerted by a victim or a third party;

- discovered crime, i.e., a result of proactive policing efforts.

Proactive efforts range from common

stop-and-searchactivities tosting operations.

Once a crime is reported or discovered, an incident is recorded by a law enforcement agency. When the perpetrator is unknown, the agency may dedicate resources to crime investigation which may lead to an arrest of a suspect.

Irrespective of whether an arrest takes place, the agency needs to decide if they will charge anybody with a crime. The period of time between pressing charges and the trial itself is commonly referred to as the pre-trial period. A judge or magistrate will usually decide on the suspect’s pre-trial custody status. Depending on the severity of the crime and their criminal history, the suspect can be released outright, released conditionally on bail, or kept in custody. If bail is set, the suspect will only be released if they can raise the required amount. At the trial, a suspect can be found guilty or not guilty, or the case may be dismissed due to other reasons. If the suspect is found guilty, a sentence will be decided by a judge or magistrate. Charges turn into convictions if and when the court finds the suspect guilty.

The sentence may include one or a combination of:

- a custodial sentence to be spent in jail (if under 12 months) or in prison;

- a period of probation with specified conditions;

- a monetary fine or compensation;

- a caution.

Sentencing guidelines may indicate the minimum and maximum terms for the sentence, including limits on the time of imprisonment and the amount that can be set for monetary fines.3 The minimum sentence may depend on the criminal history of the offender. If the sentence does include an incarceration period, once the minimum period of incarceration has elapsed, the individual may be granted parole, and released on probation before serving their full sentence. For long sentences, a decision about whether to grant parole may take place periodically.

-

Miri Zilka, Holli Sargeant, Adrian Weller. Transparency, governance, and regulation of algorithmic tools deployed in the criminal justice system: A UK case study. AIES 2022. ↩

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Criminal Justice System Flowchart. ↩

-

Sentencing guidelines can be advisory (e.g., Federal Sentencing Guidelines), which means that the judge does not have to adhere to the recommended sentencing. ↩